January 6, 2018 compression elias-fano data structures

In the previous post we discovered how to compress a set of integers by representing it as a bitmap and then compressing the latter using a succinct representation.

This post instead is about compression of monotone non-decreasing integers lists by using Elias-Fano encoding. It may sound like a niche algorithm, something that solves such an infrequent problem, but it is not like this. Inverted indexes 1, which is the most common data structure used by search engines to index their data, are made of lists of increasing integers corresponding to the documents of the collection. I might write again in the future about inverted indexes in a more comprehensive way if this is a topic of your interest, in that case please let me know with a comment.

Elias-Fano encoding has been proposed independently by Peter Elias and Robert Mario Fano during the 70s, but their usefulness has been rediscovered recently. Elias-Fano representation is an elegant encoding scheme to represent a monotone non-decreasing sequence of n integers from the universe [0 . . . m) occupying \(2n + n⌈\log{\frac{m}{n}}⌉\)bits, while supporting constant time access to the i-th element.

If we compare Elias-Fano encoding space requirement with the theoretical lower bound we realize that this structure is close to the bound, so it has been epithet quasi-succint index2.

In the Elias-Fano representation each integer is first binary encoded using \(⌈\log{m}⌉\) bits. Each binary representation of the elements is split in two: the higher part consisting of the first (left to right) \(⌈\log{n}⌉\) bits and the lower part with the remaining \(⌈\log{m} - \log{n}⌉ = ⌈\log{m/n}⌉\). The concatenation of the lower part of each element of the list is the actual stored representation and takes trivially \(n \log{m}\) bits. The higher part, instead, is a unary representation, specifically a bit-vector of size \(n + m/2^{⌈\log{m/n}⌉} = 2n\) bits. It is constructed starting from and empty bit-vector, we add a 0 as a stop bit for each possible value representable with the bits of the higher part length, we add a 1 for each value actually present positioning it before the correct stop bit. This makes clearer why we use exactly 2n bits, one bit set to 1 for the n elements and one 0 bit for all the possible distinct values obtainable with \(⌈\log{n}⌉\) bits. Finally, the Elias-Fano representation is the bitvector resulting from the concatenation of the higher and the lower part.

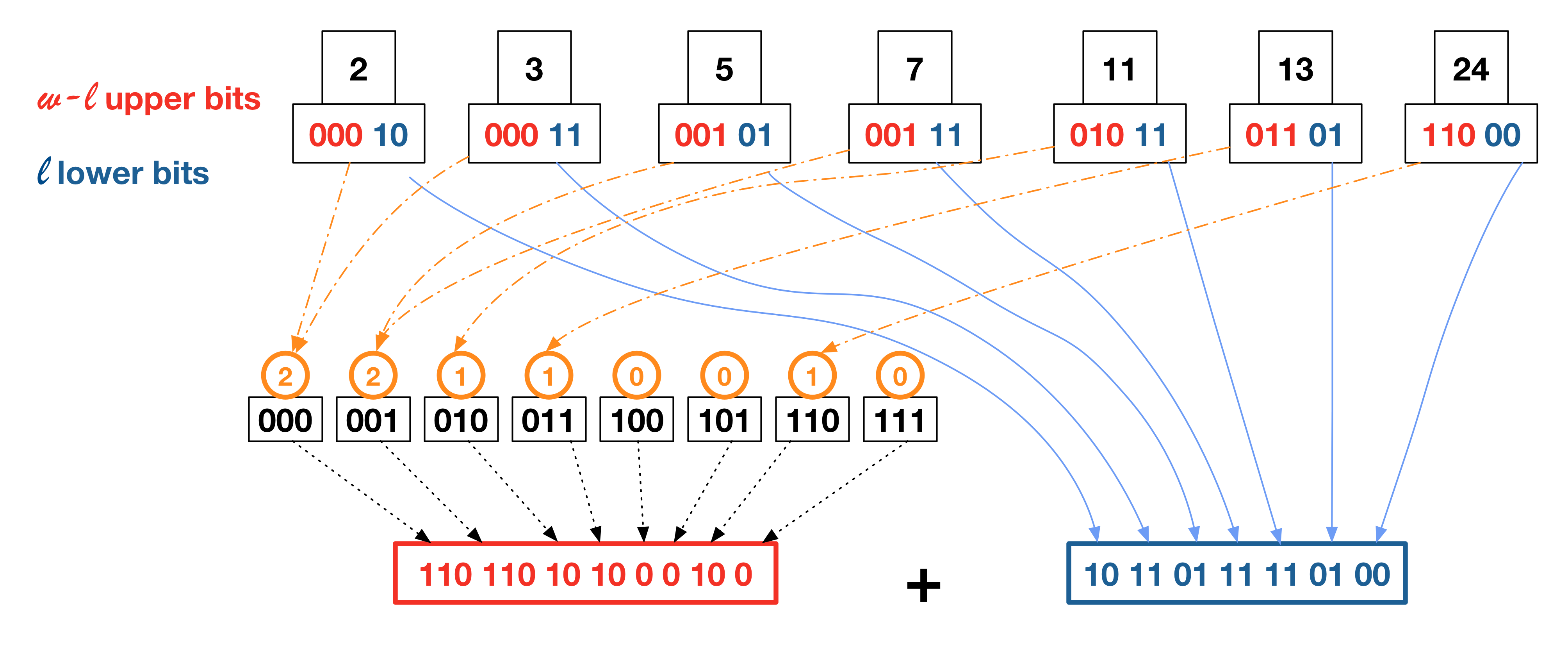

Figure 1: An example of Elias-Fano encoding of a sorted integer sequence.

As an example, lets take the sorted list of {2,3,5,7,11,13,24} as shown in Figure 1. In this case we know that m (the universe of the list) is equal to 24 and to represent all the elements in fixed-length binary we need 5 bits per element.

Then we want to split the binary representation of each element in two parts, the higher and the lower. Since we have 7 elements in total, we will use 3 bits for the higher part and 2 for the lower one as explained previously. If we consider 2 => 0b00010 we will have 000 and 10 respectively.

We repeat this process for every element of the list and we concatenate all the lower parts together.

Regarding the higher bits, since we use 3 bits per element we can imagine to have \(2^3\) buckets and we associate a counter to each bucket corresponding to the cardinality of that bucket. For 2 we will increment the 000 bucket. To the same bucket goes 3, while 5 will increment 001 and so on and so forth. There might be cases where the counter of the bucket is equal to zero, as it is for 100 in Figure 1.

Finally, we use unary encoding to represent the buckets’ counters, specifically we append as many 1-bits as the counter value of each bucket followed by a 0-bit.

In the case of the 000 bucket we will add 2 set-bits and an unset one to separate the following bucket.

The final Elias-Fano encoding is obtained by concatenating higher and lower bits just obtained.

Query

Now, we show how to get an element given the information we have. Interestingly, with this type of encoding, we can have random access for both Access and NextGEQ operations in nearly constant time.

Access

Access(i) is the operation of retrieving the element at position i from the original list of elements.

To get the lower part we can simply jump to the corresponding bits since we know the length stored for each element. To compute the higher part we need to perform a select_1(i) - i, where select_1(i) is defined as the operation which returns the position of the i-th set-bit and there are techniques to perform it in nearly constant time 3.

NextGEQ

Another interesting operation is NextGEQ(x), which returns the next integer of the sequence that is greater or equal than x. We retrieve the position p by performing select_0(hx) − hx where hx is the bucket in which x belongs to. At this point, we start to scan the elements from position p and we stop at the first one greater than x. The scan can traverse at most the size of the bucket.

Conclusion

Elias-Fano is a very effective encoding algorithm as it allows to randomly access the sequence without decoding it and in constant time. As highlighted in academic literature 4 Elias-Fano demonstrates its power in particular in list intersection overcoming any other form of compression.

Implementations

I would like to point out my Golang implementation (https://github.com/amallia/go-ef) of Elias-Fano, which is still in early stage. Feel free to get involved in the development.

A very good implementation is the one from Facebook present in Folly (https://github.com/facebook/folly/blob/master/folly/experimental/EliasFanoCoding.h).

Leave me a comment if you have written your own implementation and I will be more than happy to add it to the list.

References

-

Justin Zobel and Alistair Moffat. 2006. Inverted files for text search engines. ACM Comput. Surv. 38, 2, Article 6 (July 2006). ↩

-

Sebastiano Vigna. 2013. Quasi-succinct indices. In Proceedings of the sixth ACM international conference on Web search and data mining (WSDM ‘13). ACM, New York, NY, USA, 83-92. ↩

-

Sebastiano Vigna. 2008. Broadword implementation of rank/select queries. In Proceedings of the 7th international conference on Experimental algorithms (WEA’08), Catherine C. McGeoch (Ed.). Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, 154-168. ↩

-

Jianguo Wang, Chunbin Lin, Yannis Papakonstantinou, and Steven Swanson. 2017. An Experimental Study of Bitmap Compression vs. Inverted List Compression. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM International Conference on Management of Data (SIGMOD ‘17). ACM, New York, NY, USA, 993-1008. ↩